15,000 Somalis ‘heartbroken’ by Trump refugee ban

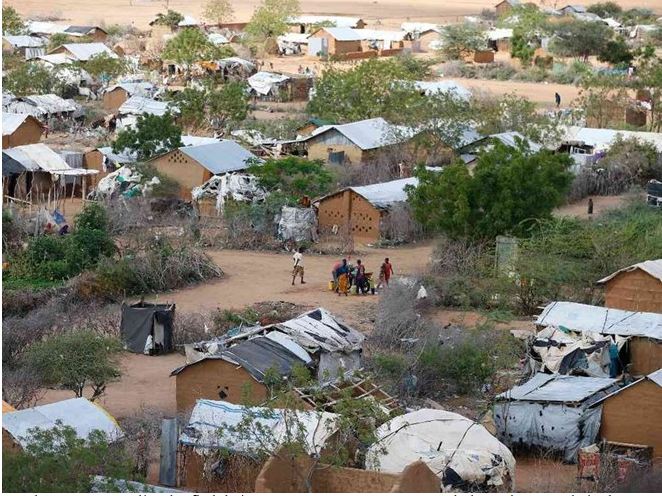

Nearly 15,000 Somalis who fled their war-torn country to Kenya and planned to resettle in the United States are now stuck in the world’s largest refugee camp because President Trump suspended the U.S. asylum program.

They include 137 refugees who just days ago thought they would be boarding flights to the U.S. Now they are gripped with “fear, devastation, worry, panic and heartbrokenness,” said Yvonne Ndege, a spokeswoman for the United Nations refugee agency.

Hardly anyone in the world is more desperate than Somalis who had hoped to escape brutal warfare and crippling poverty in their chaotic nation. Now those hopes are on hold after Trump signed an executive order Friday that suspended entry of refugees into the U.S. for 120 days to ensure that terrorists don’t sneak into the country posing as asylum seekers.

Ahmed Ismail Shafat, 25, who was born and raised in the Dadaab refugee camp on the Kenya-Somalia border, was supposed to leave Monday for London, then on to Chicago and finally Kansas City, Mo., to be resettled.

Instead, he was part of the group attending a town hall meeting Tuesday with U.N. and U.S. officials at a transit center.

The refugees who were to be resettled in the U.S. have undergone a very, very rigorous process before being identified for resettlement in the U.S.,” Ndege said. “They undergo numerous security checks involving several U.S. agencies and are subject to the highest category security checks of any traveler to the U.S.”

Shafat, who was also interviewed by officials from the Department of Homeland Security, has gone through a vetting process that took 10 years to complete. “I just got American clothing because I heard the country is very cold,” he said. “I got a big jacket in the market and told the vendor I would send money for it when I got a job in America.”

He had hoped to begin work on a college degree in math and get a job on the side to send money back to his mother in the refugee camp.

Many at the transit center had spent the previous week preparing to leave for America, completing medical checkups and getting a cultural orientation of the United States. Suleimn Yussuf Muhumed, 24, arrived at the transit center a week ago and was supposed to begin cultural orientation on Friday — the day Trump signed the travel ban.

Instead, he said officials in the center called a meeting and “told only people who were going to America to stay for the meeting. That’s when I could tell it was not normal, something was wrong.”

After he learned about the ban, Muhumed called his father, who is in Dadaab and planned to join Muhumed in Ohio on Valentine’s Day. His dad had fled Somalia with Muhumed and his younger sister after armed men killed two of his brothers and one sister. A drought later devastated his small plot of land.

Muhumed said life in the refugee camp is “filled with difficulties.” But he heard Ohio “is a very cool place, a very nice place for life, and the people are very welcoming.”

According to the U.N., at least 26,000 refugees in Kenya were in the process of resettlement to the U.S. and are affected by the executive order — 14,500 of them from Dadaab.

The Kenyan government announced last May plans to close the camp, a move criticized by humanitarian agencies. The government later backed away, though the future of the camp remains a source of constant stress to the Somali refugees.

Even after Tuesday’s town hall meeting, refugees living in this Kenyan capital continued to arrive at the center looking for answers from immigration officials.

Farhiyo Hassan, who was supposed to fly Tuesday evening, begged a security guard to gain access to officials with answers as to whether she would still be able to travel.

“My husband is there already,” Farhiyo said. “I was feeling so happy, so good that I could go, but now I don’t know what is happening.”

Farhiyo came to Kenya four years ago after her father was killed by the al-Qaeda linked al-Shabab militant group, which controls swaths of Somalia. As she pleaded to get information, a young Somali man who also just learned he would not be able to travel to the U.S. broke down in tears, seeking solace in the arms of a fellow refugee.

“It’s really important to understand that (the U.N.) only puts forward resettlement candidates who are the most vulnerable people in the world, survivors of torture and rape and abuse,” U.N. spokeswoman Ndege said.

“The U.S. resettlement program is one of the most important in the world,” she added. “We can only hope the U.S. will continue its long tradition of helping those fleeing persecution.”

USA Today