Border Wall Would Cleave Tribe, and Its Connection to Ancestral Land

The phone calls started almost as soon as President Trump signed his executive order, making official his pledge to build a wall to separate the United States from Mexico.

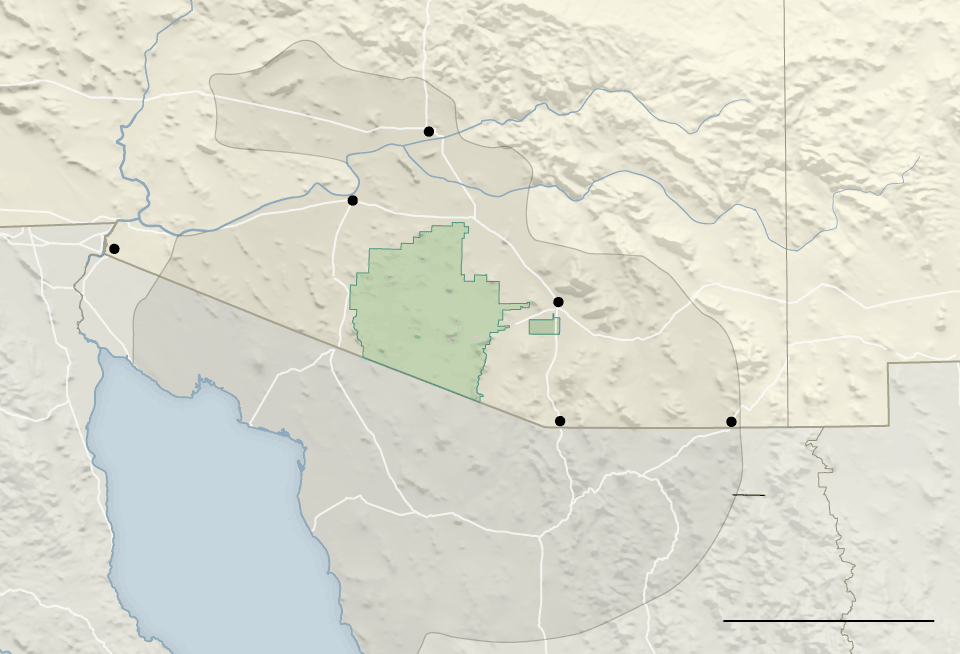

Verlon M. Jose, vice chairman of the Tohono O’odham Nation, whose reservation extends along 62 miles of the border, heard from people he knew and those he had never heard of. All of them were outraged and offered to throw their bodies, Standing Rock-style, in the way of any construction that would separate the tribe’s people on the north side of the border and the south side, where they live in six villages within the boundaries of the group’s ancestral lands.

“If someone came into your house and built a wall in your living room, tell me, how would you feel about that?” Mr. Jose asked in an interview last week. He spread his arms, as if embracing the ground that stretched before him, a rugged expanse of crackled dirt speckled in saguaros, and said, “This is our home.”

Mr. Trump’s plan to build a 1,954-mile wall from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico will have to overcome the fury of political opponents and numerous financial, logistical and physical obstacles, like towering mountain ranges.

Then there are the 62 miles belonging to the Tohono O’odham, a tribe that has survived the cleaving of its land for more than 150 years and views the president’s wall as a final indignity.

A wall would not just split the tribe’s traditional lands in the United States and Mexico, members say. It would threaten an ancestral connection that has endured even as barriers, gates, cameras and Border Patrol agents have become a part of the landscape.

“Our roots are here,” Richard Saunders said, standing by a border gate in San Miguel, which he and his wife pass through — when it is open — to visit her grandparents’ graves, 500 yards into Mexico. “Our roots are there, too, on the south side of this gate.”

The Tohono O’odham — they call themselves “desert people” — have been around since “time immemorial,” Mr. Jose likes to say; they and their predecessors were nomads in the region for thousands of years, roaming for water and food on mountains and lowlands.

After the Mexican-American War and then the Gadsden Purchase in 1854 delineated the border for good, most of the tribe’s land was left in present-day Arizona, where it still controls 2.8 million acres — a territory about the size of Connecticut — while a smaller piece became part of what is now the Mexican state of Sonora.

The tribe has 34,000 enrolled members, according to its chairman, Edward D. Manuel. Half live on the reservation in Arizona, 2,000 are in Mexico and the rest left for places where job prospects were better. Those who have stayed might work for the tribal government, its Desert Diamond Casino, the schools or businesses like the Desert Rain Cafe, which serves chicken glazed in prickly pear and smoothies made from saguaro fruit, on Main Street in Sells, the reservation’s largest community.

The Tohono O’odham (pronounced Toh-HO-noh AW-tham) reservation has been a popular crossing point for unauthorized migrants and one of the busiest drug-smuggling corridors along the southern border, in part because the federal government strengthened the security at other spots. While a 20-foot-tall steel fence lines the border in San Luis, Ariz., to the west, and Nogales, Ariz., to the east, here the border is a lot more permeable, guarded by bollards and Normandy barriers measuring eight feet, maybe, and, in some areas, sinking in the eroding ground.

Erosion is one of the challenges to any wall. The border here is also sliced by mountains and carved by dry creek beds that turn into rushing rivers during the summer’s monsoon rains.

Tohono O’odham leaders acknowledged that they were straddling a bona fide national security concern. The tribe reluctantly complied when the federal government moved to replace an old barbed-wire fence with sturdier barriers that were designed to stop vehicles ferrying drugs from Mexico. It ceded five acres so the Border Patrol could build a base with dormitories for its agents and space to temporarily detain migrants. It has worked with the Border Patrol; hardly a day goes by without a resident or tribal police officer calling in a smuggler spotted going by or a migrant in distress, said Mr. Saunders, the director of public safety.

The tribe regularly treats sick migrants at its hospital and paid $2,500 on average for the autopsies of bodies of migrants found dead on its land, mostly from dehydration. (There were 85 last year, Mr. Saunders said.)

The number of apprehensions on the reservation has also dropped — to 14,000 last year from 85,000 in 2003, according to the tribe’s public safety department. Still, the vehicle barriers, installed in 2006, created new headaches. One rancher, Jacob Serapo, used to fetch water for his family and cattle from a well 100 yards from his home, but the barriers left the well on the other side, in Mexico. Now he must drive four miles a few times each week to the nearest water source on the United States side.

“There is no O’odham word for wall,” Mr. Serapo said. (There is also no word for “citizenship.”)

The current border barriers have three gates that open regularly for family reunions and ceremonies like the Vikita (pronounced WHI-kih-tha), celebrated every summer to mark the tribal new year, and religious pilgrimages 60 miles into Mexico. Those who live on the Mexican side have border-crossing cards authorizing them to visit the tribe’s American side, but not to stay or work in the United States, or leave the reservation.

The Border Patrol has checkpoints on each of the roads leading out of the reservation, where a tribal member who is a Mexican citizen could be detained and deported, Mr. Saunders said.

Because of tribal rights, building a wall across the lands of the Tohono O’odham Nation would most likely require an act of Congress, according to Monte Mills, co-director of the Margery Hunter Brown Indian Law Clinic at the University of Montana.

But the Supreme Court has held that, in considering whether to act in ways that have an impact on Native Americans, Congress must partake in a “detailed consideration of tribal interests,” Mr. Mills said. Last week, Mr. Manuel and Mr. Jose met with Homeland Security officials in Washington to ask for a seat at the table.

When asked about the tribe’s concerns, Gillian Christensen, a spokeswoman for Homeland Security, said the agency “is working to implement the guidance given in the president’s executive order.”

“When we have more info to share on plans,” Ms. Christensen said, “we will.”

If Mr. Trump sought to build the wall without the approval of Congress, the project could be more vulnerable to legal action, said Mr. Mills. Still, many Native Americans saw the president’s swift decision to resume work on the Dakota Access oil pipeline — which President Barack Obama had halted after protests at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota — as a sign that the new administration would be less deferential to their sovereignty.

As the sun set on Friday, dozens of Tohono O’odham members filled the Legislative Council chambers at the White House, the building in Sells that is home to the tribal government, for a community meeting about the border wall. Inside, volunteers registered people to vote and instructed them on how to write letters to the state’s congressional delegation.

“If we have a wall, it will separate our people,” said the meeting’s main organizer, April Ignacio, 34, in an interview outside the building.

She then brought up another possibility that filled her with dread. “If we don’t have a wall and other parts of the border have, the cartels will funnel everything through here,” she said. “What will that do to us?”

New York Times