Bug-killing book pages clean murky drinking water

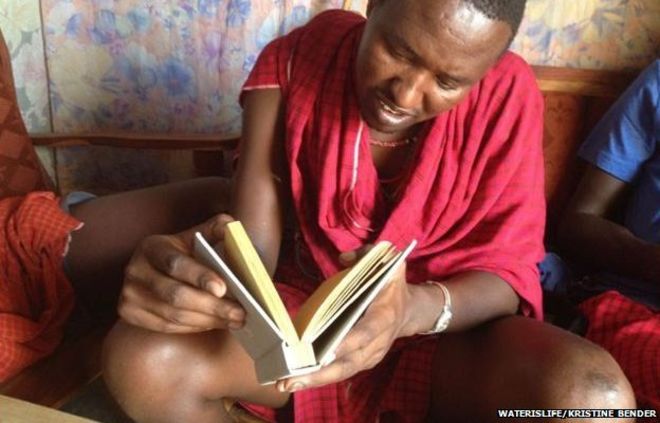

The “drinkable book” combines treated paper with printed information on how and why water should be filtered.

Its pages contain nanoparticles of silver or copper, which kill bacteria in the water as it passes through.

In trials at 25 contaminated water sources in South Africa, Ghana and Bangladesh, the paper successfully removed more than 99% of bacteria.

“A book with pages that can be torn out to filter drinking water has proved effective in its first field trials.’

The resulting levels of contamination are similar to US tap water, the researchers say. Tiny amounts of silver or copper also leached into the water, but these were well below safety limits.

The results were presented at the 250th national meeting of the American Chemical Society in Boston, US.

Dr Teri Dankovich, a postdoctoral researcher at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, developed and tested the technology for the book over several years, working at McGill University in Canada and then at the University of Virginia.

“It’s directed towards communities in developing countries,” Dr Dankovich said, noting that 663 million people around the world do not have access to clean drinking water.

“All you need to do is tear out a paper, put it in a simple filter holder and pour water into it from rivers, streams, wells etc and out comes clean water – and dead bacteria as well,” she told BBC news.

The bugs absorb silver or copper ions – depending on the nanoparticles used – as they percolate through the page.

“Ions come off the surface of the nanoparticles, and those are absorbed by the microbes,” Dr Dankovich explained.

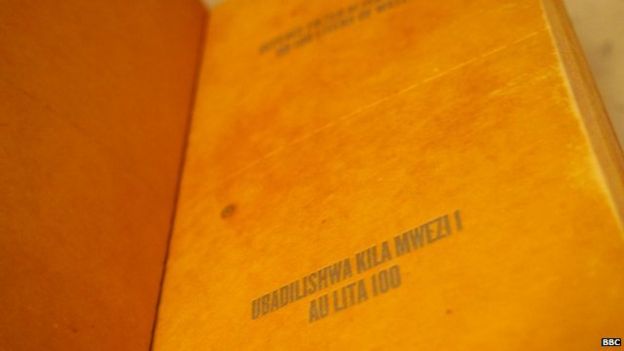

According to her tests, one page can clean up to 100 litres of water. A book could filter one person’s water supply for four years.

Dr Dankovich had already tested the paper in the lab using artificially contaminated water. Success there led to the field trials which she conducted over the past two years, working with the charities Water is Life and iDE.

In these trials, the bacteria count in the water samples plummeted by well over 99% on average – and in most samples, it dropped to zero.

“Greater than 90% of the samples had basically no viable bacteria in them, after we filtered the water through the paper,” Dr Dankovich said.

“It’s really exciting to see that not only can this paper work in lab models, but it also has shown success with real water sources that people are using.”

One location gave the paper a particularly tough challenge.

“There was one site where there was literally raw sewage being dumped into the stream, which had very high levels of bacteria.

“But we were really impressed with the performance of the paper; it was able to kill the bacteria almost completely in those samples. And they were pretty gross to start with, so we thought – if it can do this, it can probably do a lot.”

More work to to

Dr Dankovich and her colleagues are hoping to step up production of the paper, which she and her students currently make by hand, and move on to trials in which local residents use the filters themselves.

“We need to get it into people’s hands to see more of what the effects are going to be. There’s only so much you can do when you’re a scientist on your own.”

For example, Dr Dankovich’s work with iDE in Bangladesh has explored whether a filter, holding one of the book pages, could be fitted into a “kolshi” – the traditional water container used by many Bangladeshis.

Dr Daniele Lantagne, an environmental engineer at Tufts University, said the data from the trials showed promise.

“There’s a lot of interest in developing new products for point-of-use water treatment,” she told the BBC.

The “drinkable book” has now passed two key stages – showing that it works in the lab, and on real water sources.

Next, Dr Lantagne said, the team will need “a commercialisable, scalable product design” for a device that the pages slot into.

She also said that while the paper appears to kill bacteria successfully, it is unclear whether it would remove other disease-causing micro-organisms.

“I would want to see results for protozoa and viruses,” she said.

“This is promising but it’s not going to save the world tomorrow. They’ve completed an important step and there are more to go through.”

Dr Kyle Doudrick studies sustainable water treatment at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. He agreed that the book system would be especially powerful if it could also tackle non-bacterial infections, such as the tiny parasite cryptosporidium which recently caused a health scare in Lancashire.

He also said it would be important to make sure people understood how to use the filters – and how often to change them. But he was encouraged by the trial results.

“Overall, out of all the technologies that are available – ceramic filters, UV sterilisation and so on – this is a promising one, because it’s cheap, and it’s a catchy idea that people can get hold of and understand.”