Focus on Migration: Tap LinkedIn for data gold dust

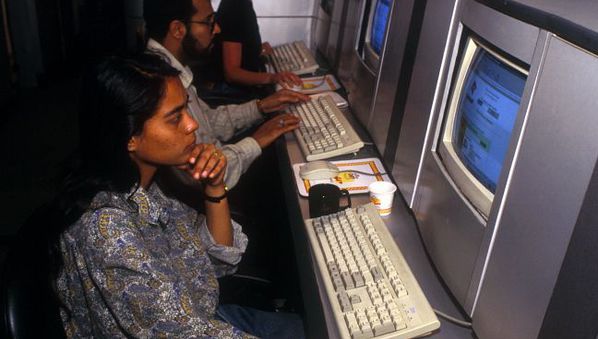

Social networking sites are a treasure trove of data on professional migration, says Carlos Vargas Silva.

South Africa’s former president, Thabo Mbeki, recently declared that the number of skilled people and professionals leaving Africa each year is “truly frightening”.

“It is estimated that more African scientists and engineers live and work in the USA and the UK than anywhere else in the world,” he said.

Mbeki is not the only one worrying about the movement of highly skilled workers across countries. It has become a hot topic in policy circles in recent years and the loss of scientists topped the agenda at the Africa Universities Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, earlier this month.

“It is estimated that more African scientists and engineers live and work in the USA and the UK than anywhere else in the world.” Thabo Mbeki

There is no consensus on what makes for an adequate policy response to the departure of the “best and brightest”. Some have fervently argued that it is wrong to deplete countries of their most gifted workers; others strongly defend the right of people to leave their countries in search of better opportunities. But, whatever the view, the fact is there is very limited information on the actual migration patterns of highly skilled individuals.

Most countries do not systematically collect information on the characteristics — such as education and work experience — of the people who move across their borders. Their information often comes from population censuses, usually only conducted once every ten years, or from more frequent, but smaller scale, surveys.

As such, either the analysis quickly becomes out of date or it is based on a small sample which might not represent the target population — that is, highly skilled migrants. Most of the academic evidence on highly skilled migration describes only a few professions and countries, with African doctors being a particularly popular subject for analysis.

But there is up to date information on these migration patterns. Recently, researchers at the 300 million-member social networking site LinkedIn used data on the movement of its members to provide a picture of which countries are losing professionals, and which are gaining them. [1]

Data on the 20 countries that saw the greatest migration activity — both inwards and outwards — among LinkedIn members in 2014 led the researchers to estimate that the United Arab Emirates gained the most professionals from migration. The difference between the arrival and departure of LinkedIn members to and from the United Arab Emirates was equivalent to 1.9 per cent of the total LinkedIn country membership. At the other end of the scale, India lost the most from migration: the equivalent of 0.2 per cent of the country’s membership.

Clearly this isn’t a fail-safe system for analysis: LinkedIn use is self-selecting so what counts as ‘professional’ will vary from country to country. But even broad brushstrokes are better than the blurred picture governments are currently faced with.

The researchers are also able to determine where people are moving to. Some 40 per cent of members who left India moved to the United States, for example. LinkedIn datasets also contain abundant information on those who migrate, such as their level of education. [2]

This information could prove vital to governments: it’s essential to measure and understand the movement of highly skilled workers so that countries can draw up suitable policy responses. And, in a world of frequent population movement, information needs to be updated regularly if it is to be useful.

Keeping track of migrants’ skills, education, experience and location is expensive and time-consuming. But social networks prompt people to do just this – and voluntarily. If countries want more information, they should work more closely with social media companies, and could even create their own social networking products, encouraging members to include and update their information.

Carlos Vargas-Silva is an associate professor and senior researcher at theCentre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS) at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom, where he leads a project examining the impacts of forced migration on labour markets. He has also acted as a consultant on migration for the World Bank and the UN University, among others. He can be contacted on Twitter: @CVar_Sil

SciDev