How U.S. regulation may keep remittances from some Somali families

Behind this row of unassuming storefronts on Minneapolis’

Behind this row of unassuming storefronts on Minneapolis’

East 24th Street lies a little slice of Somalia. Dozens of shops sell scarves and books, fried snacks and sweet Somali tea. Pretty much everything you can buy in Mogadishu but in the heart of Minnesota.

Maryan Abdi moved here from Somalia seventeen years ago and runs one of those shops.

I sell rugs and flowers, she says. And it’s not just to support her family in the US.

STEPHEN FEE: “So who do you send money to at home? Who is still in Somalia in your family?”

My brothers, uncles, and aunts, she says. Each month she sends anywhere from three to five hundred dollars to family and friends back home.

STEPHEN FEE: “So this shop basically helps support not just your family, but your family, their neighbors, their friends. I mean, all from here basically.”

Yes, she says, the whole family. I have this business, and I have to help them.

Maryan Abdi is one of 85-thousand Somali-Americans in the U-S, roughly a third of whom live in Minnesota. The majority fled East Africa after Somalia’s civil war in the 1990s.

According to community leaders in Minneapolis-St. Paul, 80 percent of the Somali-Americans here send money back to East Africa. Aid groups say 40 percent of Somalia’s population relies on those dollars — known as remittances — to survive.

Mohamed Idris runs ARAHA, the American Relief Agency for the Horn of Africa, based in Minneapolis.

MOHAMED IDRIS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ARAHA: “It is estimated about $1.3 billion dollars are the — the amount of money that come on an annual basis to Somalia from Somalis in diaspora. So the remittance is the lifeline, is the backbone for Somalia.”

STEPHEN FEE: But now, the $215 million dollars that flow from the Somali diaspora in the U-S each year may be in jeopardy. The U-S government is increasingly concerned some of those remittances are going to terror groups that have taken hold in Muslim-majority Somalia, particularly al Shabaab — an al Qaeda linked organization behind an assault on a Kenyan university this April that killed more than 140 people and an attack on a Kenyan mall two years ago that killed 67.

Adam Szubin is the U-S Treasury Department’s acting Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence.

ADAM SZUBIN, ACTING UNDER SECRETARY, U.S. TREASURY: “Any time you’re talking about funds transfer mechanisms, whether it’s wires, whether it’s the baking system, any funds transfer can be exploited by bad actors, including terrorist groups. And obviously when you’re talking about Somalia, al Shabaab has a presence there, and it’s had a very harmful influence on the people of Somalia.”

STEPHEN FEE: As a result, Treasury has imposed stricter controls on money transfers to Somalia, where there’s a weak central bank and limited financial oversight.

ADAM SZUBIN, ACTING UNDER SECRETARY, U.S. TREASURY: “The key issue for us is the strength of the financial mechanism, making sure that we try to keep bad flows out of U-S banks, out of the U-S financial system, and thereby deprive the terrorist actors of their livelihood.”

STEPHEN FEE: But according to Ryan Allen, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs, Treasury’s strict anti-money laundering rules are having the inadvertent effect of pressuring banks that normally help facilitate remittances to Somalia.

RYAN ALLEN, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA HUMPHREY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS:

“Because of the expectations on the due diligence, the banks run a risk. If the money should fall into the wrong hands, despite their best efforts even, they can face some really significant penalties, you know, in the millions of dollars kinds of penalties.”

STEPHEN FEE: “With that in mind, these intermediary banks that hold the accounts for these money transfer organizations, started closing some of these accounts?”

RYAN ALLEN, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA HUMPHREY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS:

“That’s right. So slowly, one by one, and then — and then a kind of rash of closings, many of the — many of the banks are deciding that the risk is not worth the return.”

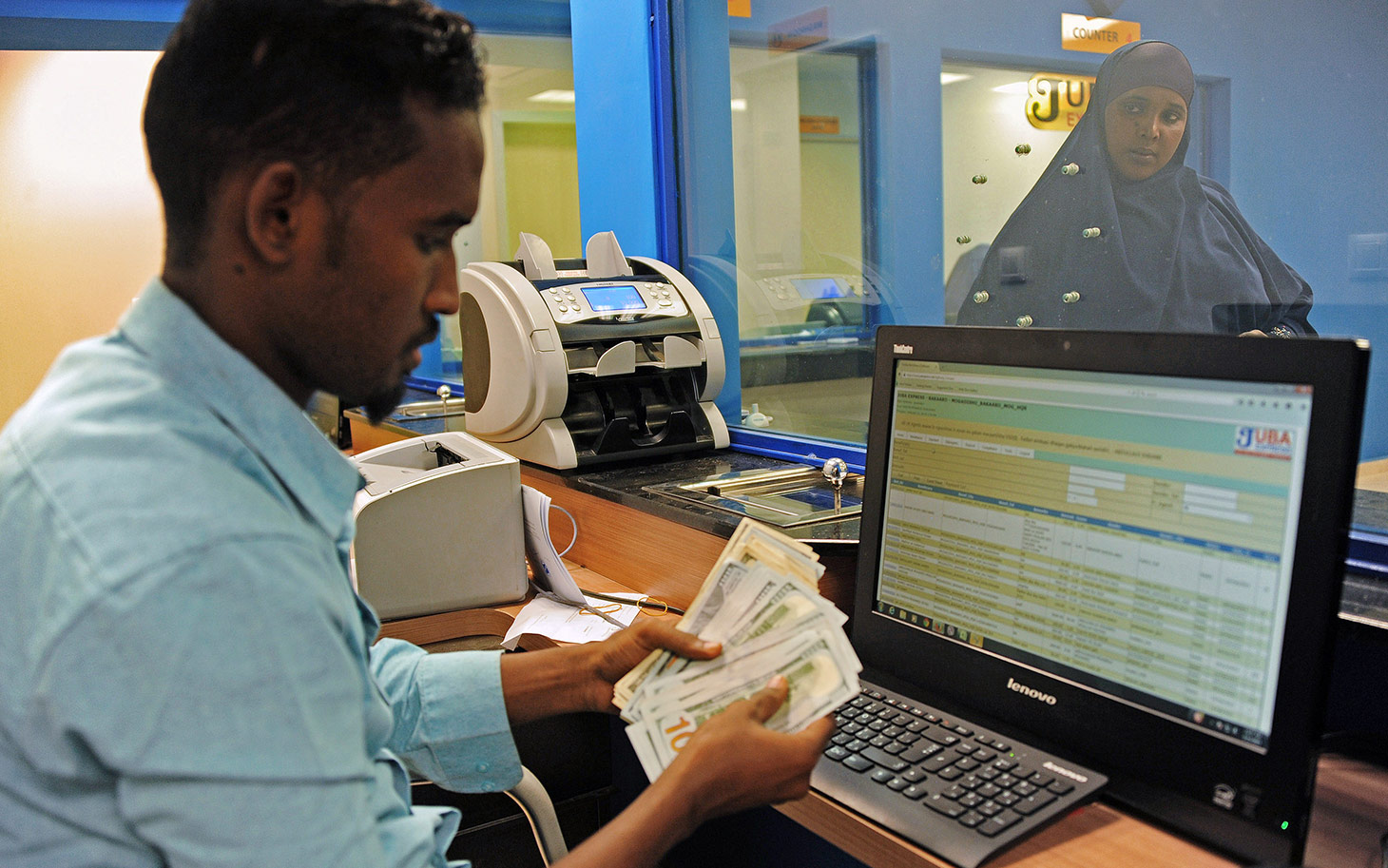

STEPHEN FEE: Money transfers to Somalia are complex. Senders, say in Minneapolis, bring cash to a money transfer window. The money is then held in an intermediary bank, wired through a clearinghouse in the Middle East, and finally winds up in East Africa. But if the money ends up in the wrong hands, the intermediary banks may he held responsible.

This February, one of those institutions — Merchants Bank of California, responsible for up to 80 percent of US-to-Somalia remittances — decided to get out of the business.

MOHAMED IDRIS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ARAHA: “Right now, for regular Somalis in the Twin Cities, the number of remittance, Somali remittances that are doing this business are shrinking.”

STEPHEN FEE: Mohamed Idris, whose group has offices throughout East Africa, is still able to send money to his colleagues in Somalia, but the remittance firms in Minneapolis are capping amounts he can send abroad and charging higher fees.

MOHAMED IDRIS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ARAHA: “Remember, there is no traditional bank in Somalia. And — and that’s — even the U-N uses these wire transfers because that’s the — it’s the only means to send money to Somalia. Businesses, charities, government.”

STEPHEN FEE: But some of those dollars have made their way from the US to militant groups in Somalia.

In 2011, two Somali-American women from Rochester, Minnesota were convicted of sending 86-hundred dollars to al Shabaab. That same year, a Somali cab driver in St. Louis pleaded guilty to providing 6-thousand dollars to help al Shabaab buy a vehicle. And in 2013, a jury in San Diego found four Somali men guilty of conspiring to raise funds for the terror group.

RYAN ALLEN, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA HUMPHREY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS:

“So far, the U-S government has only been able to find some isolated cases of this, right. And so how much more widespread it might be is really hard to determine.”

STEPHEN FEE: Acting Treasury Under Secretary Adam Szubin won’t say exactly how much money he believes has made its way from the U-S to Al Shabaab. But his concern lies with the lack of any formal banking infrastructure on the Somali side of remittance transactions.

ADAM SZUBIN, ACTING UNDER SECRETARY, U.S. TREASURY: “And so what we’re talking about is a very opaque — if you will, a black hole — where those funds are going. That’s the root concern of banks who are asking hard questions about how do we know the funds are going where they’re supposed to be going?”

STEPHEN FEE: Money transfer offices in the US can check the names of money senders and recipients against a government list of known terrorist supporters. But their counterparts in East Africa have no such ability.

Abdulaziz Sugule runs a trade group for money transfer offices in Minnesota.

STEPHEN FEE: “How do you know that some of this money might not eventually get into the wrong hands?”

ABDULAZIZ SUGULE, SOMALI AMERICAN MONEY SERVICE ASSOCIATION: “They know their customers. They know people who send money. If they see something’s happening, they can also — there’s a way you can report to the government.”

STEPHEN FEE: Sugule says lack of transparency is an issue — but the risk is negligible.

ABDULAZIZ SUGULE, SOMALI AMERICAN MONEY SERVICE ASSOCIATION: “If you look at the average person sending, if you look at that, it’s going to be 200, less than $200 dollars. And that money’s going to the needy people, the people in refugee camps, the people who are destitute.”

STEPHEN FEE: And Somali-Americans like 24-year-old truck driver Abdi Salad say they’re as concerned as the U-S- government about militant groups back home. After all, their families are in danger.

ABDI SALAD: “We’re not terrorists. We’re not supporting terrorists. We just want to send money to our families.”

STEPHEN FEE: Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges has teamed up with her state’s congressional delegation to press for a national solution — one that balances security concerns with her constituents’ desires to aid their families.

MAYOR BETSY HODGES, MINNEAPOLIS, MN: “It’s a question of banks, federal regulators, the State Department, Treasury working together to find solutions that will both keep our country secure and keep the world secure as we should and as we must. But that would also allow folks to send dollars back home. And frankly, not being able to send dollars back home, in some ways, is a larger security issue. It gives a reason for people to say, at one point you had access to resources from home, now you don’t, the west doesn’t care about you. Which you know, we don’t need to add to that pile of messages.”

STEPHEN FEE: In Washington, Minnesota Congressman Keith Ellison has taken up his constituents’ concerns as well. He’s proposed reducing the liability for banks that facilitate remittances — so if money goes to the wrong people, the banks would face less severe punishment from regulators.

STEPHEN FEE: “Couldn’t that help at least loosen up the gears a little bit?”

ADAM SZUBIN, ACTING UNDER SECRETARY, U.S. TREASURY: “I don’t think that’s the answer, in that it’s not a question of regulatory liability. Banks don’t want to be handling money flows if they don’t know where they’re going, especially into a high-risk area like Somalia, and we can’t be in the practice of saying you don’t have to worry about your anti-money laundering or counter-terrorist financing regulatory obligations.”

STEPHEN FEE: The Treasury Department and other U-S agencies are working to strengthen banking oversight in Somalia. University of Minnesota professor Ryan Allen says THAT could reduce the risk of money ending up in terrorists’ hands and help keep the remittance pathway open.

RYAN ALLEN, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA HUMPHREY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS:

“If we have a well-established and strong central bank in Somalia, if we have a banking sector that is capable of doing assurances on who’s getting money and keeping tabs on where the money’s going, that’s the best long-term solution to this problem.”

STEPHEN FEE: But it’s the short term that has Somali-Americans in Minneapolis most concerned. And Mohamed Idris, who runs the relief agency ARAHA, says slowing the remittance flow could sabotage Somalia’s gradual steps toward greater political stability.

MOHAMED IDRIS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ARAHA: “It means that our work will be doubled. It will be — means that the fragile situation that is getting better right now in Somalia is going to reverse.”