Kenya wages war on smugglers who fund Somali Islamist militants

When Kenyan police arrested six men in the vast Dadaab refugee camp near the Somali border last April, their ultimate aim was to dismantle a decades-old sugar smuggling trade that is funding Somali militants waging war on Kenya.

When Kenyan police arrested six men in the vast Dadaab refugee camp near the Somali border last April, their ultimate aim was to dismantle a decades-old sugar smuggling trade that is funding Somali militants waging war on Kenya.

The arrests, coming weeks after four al Shabaab gunmen massacred 148 people at nearby Garissa university, were part of Nairobi’s new strategy to choke off the flow of money to Islamists whose cross-border raids have hammered Kenya and its tourism industry.

While cash from sugar smuggling may amount to only a few million dollars, experts say such sums are enough for attacks that need just a few assault rifles, transport and loyalists ready to die – such as the Garissa raid or the 2013 assault on Nairobi’s Westgate shopping mall that killed 67 people.

“It’s like the government is awakening,” said a senior Kenyan security source from Garissa region, adding the authorities had previously often “turned a blind eye to all these things because a lot of people were benefiting – but at a cost of security.”

However if a lasting impact is to be secured more must be done, say security and diplomatic sources. That includes rooting out corruption in the police force and going after smuggling cartel bosses as well as the middle men detained so far.

The move to tackle the cross-border trade may prove as vital as the military offensive against al Shabaab inside Somalia by African Union peacekeepers and Somali soldiers that has pushed the group into smaller pockets of territory.

“Unless al Shabaab sources of revenue are chopped off, we are not going to see the end of instability in south Somalia and the region,” said Rashid Abdi, a Somalia expert based in Nairobi.

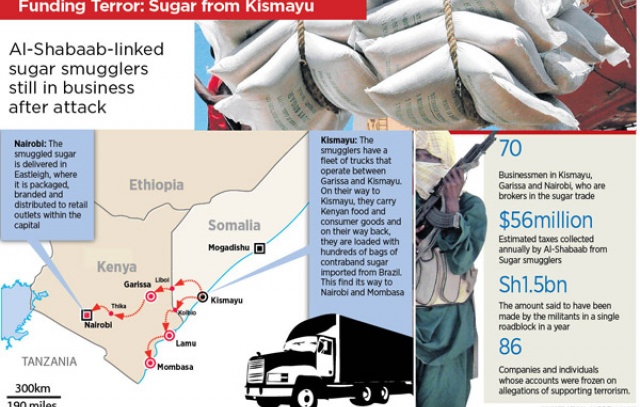

President Uhuru Kenyatta’s government has taken steps to halt the trafficking of sugar from the southern Somali port of Kismayu to Kenya’s frontier and has set up a special unit in the National Intelligence Service (NIS) to dismantle smuggling cartels, the security source said.

“SECRET” DOCUMENT

Days after the Garissa attack, Kenya published a list of 85 entities and individuals with links to al Shabaab.

That list did not elaborate on the links, but a government document marked “secret” and reviewed by Reuters detailed how 30 listed people were involved in smuggling. The six men arrested in Dadaab on April 18 were on both lists.

“The sugar barons pay illegal levies – or protection fees – to the al Shabaab who in turn uses the proceeds to fund terrorist activities/operations,” says the “secret” document, drawn up by the government on April 25.

Sugar smuggling is lucrative in Kenya, where the local industry is protected from imports as part of an agreement with Kenya’s African trading partners. So the commodity in Kenya is sold at an inflated price compared to global markets.

Diplomats acknowledge progress against smugglers has been made, but worry the authorities will not keep up the crackdown.

“Those sugar folks are connected (to the authorities), so the question is what happens going forward,” said one Western diplomat.

Adding to scepticism, only mid-level dealers have been arrested and no cartel bosses have even been named.

How the smuggling trade works and how cash is paid to two al Shabaab was explained to Reuters by two ethnic-Somali sugar smugglers from the Dadaab camp – Hussein, a trader, and Farah, a broker linking smugglers and police.

Both men joined the flood of refugees who crossed into Kenya after conflict erupted in Somalia in 1991. They agreed to meet in a secluded area in a Dadaab hotel on condition only their first names were used.

According to their accounts – corroborated by Kenyan and regional security sources – smuggled goods arrive in Kismayu port where Kenyan-owned trucks are loaded with 50-kg bags of Brazilian sugar imported from the Middle East.

CORRUPTION

From there, the trucks drive through al Shabaab-controlled territory to Kenya’s border. At one of two al Shabaab checkpoints, drivers pay $1,025 per truck to pass.

“Al Shabaab sometimes move the checkpoint,” said Hussein. “But you receive a slip from them, so you can show that if you run into them again.”

Once at Kenya’s frontier, officially shut to any traffic whether carrying goods or passengers, trucks pay 60,000 shillings ($600) each to Kenyan police to cross. Somali authorities take a separate cut along the way.

Deputy County Commissioner Albert Kimathi acknowledged some police were involved but said this was being tackled by steps such as moving officers who had been in post for three years. Those in smuggling “hot spots” could be moved after six months.

“It’s the only way not to institutionalize the corruption issue,” he said. “If someone overstays, they become so well known to the locals that they become part of the racket.”

Hussein and Farah said that, until the crackdown began in April, about 35 trucks carrying sugar, rice and other contraband arrived each week at Dadaab, home to about 350,000 refugee Somalis. They said others unloaded in Garissa and Wajir, further north, but they were not sure how many.

Based on the Dadaab business alone, and the figures for the amount earned with each truckload, al Shabaab earns about $1.9 million a year, according to a Reuters calculation.

A senior police officer in Dadaab said Kenyan smugglers “look at the money they make and don’t think about the money they give to al Shabaab, and the kind of damage that will do.”

In Dadaab, the April 18 arrests had an immediate effect, at least for a short while, by driving sugar prices higher as shops started sourcing more expensive Kenyan sugar from Nairobi.

“The fear is that if you are found with sugar you will be associated with al Shabaab,” said one local Dadaab politician, who also wanted to remain anonymous. “No one wants that.