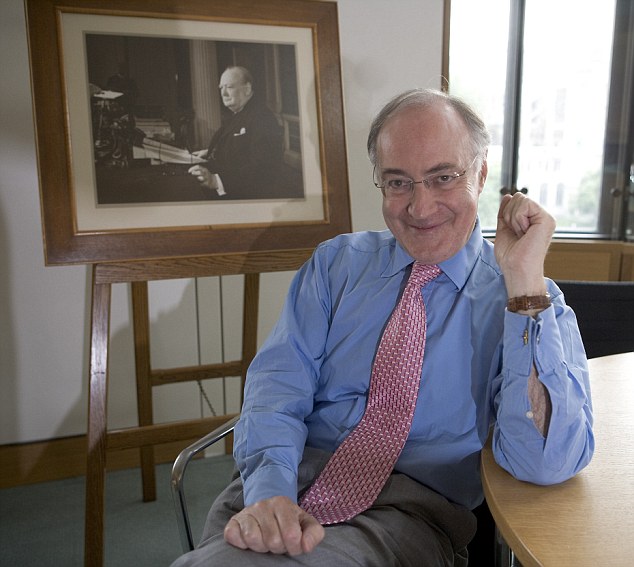

Michael Howard is a Tory giant. So how has he got entangled in a slew of doubtful companies – and a fraud probe in a war-torn hell hole?

Almost two years ago to the day, an incongruous figure stepped on to the tarmac at Aden Adde International Airport in Mogadishu.

After all, it is not every day that a 74-year-old British peer lands in the once-beautiful capital of Somalia, now a bristling nest of pirates, kidnappers and jihadists.

It turned out to be a fateful journey for Lord Howard of Lympne, better-known as Michael Howard, the former Conservative party leader.

He had travelled to the East African hell hole at the behest of his corporate paymaster, the fuel exploration company Soma Oil & Gas, where he is chairman. The result is that he has been caught up in an investigation by the Serious Fraud Office into the company.

- Lord Howard travelled to Somalia at the behest of his corporate paymaster

- He has been caught up in an investigation by the Serious Fraud Office

- Although the SFO insists he has done nothing wrong, the investigation is embarrassing

And although Soma claims the SFO insists Lord Howard has done nothing wrong, the investigation is embarrassing, to say the least.

For like many politicians, the former minister — who sacrificed an impressive legal career to serve his country in Westminster — has assembled a number of non-executive jobs to try to ensure a comfortable retirement.

And Soma is not the only company with which he is associated that has attracted controversy.

Soma is a fledgling outfit set up to explore Somalia for natural resources, and its parent company — uncomfortably for a former Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer — is based in the tax haven of the British Virgin Islands.

Howard was recruited as chairman by its founder, investment banker turned oil tycoon Basil Shiblaq. They met at a lavish party hosted by the Conservatives to woo rich businessmen as donors — functions that also serve as a ‘milk round’ for senior politicians looking for well-remunerated company directorships.

He joined the Soma board in May 2013, alongside the aristocratic Lord Paddy Gillford, the Earl of Clanwilliam, a former Tory adviser who was drafted in as a non-executive director.

It was just weeks later that Howard was put on that plane to Mogadishu. His mission: to win permission from the Somali government to start oil exploration in the war-ravaged country and its coastal waters. This would be a delicate task.

Somali ministers were reluctant to let western oil companies start possibly lucrative exploration projects because of the risk that it would stir up conflict between rival warlords, greedy for money and power.

But Lord Howard’s persuasive abilities — honed by his background as a barrister and his years in the highest echelons of politics — won the day. The Somali minister for natural resources, Abdirizak Omar Mohamed, told the Financial Times at the time that Lord Howard’s profile was key to agreeing the deal.

It may be the Tory peer — once memorably and utterly unfairly described by colleague Ann Widdecombe as having ‘something of the night about him’ — looks back on those negotiations with mixed feelings.

For now that the SFO has launched its criminal investigation into the company, Howard is bracing himself to be interviewed.

The company, whose offices were raided by fraud officers earlier this month, goes out of its way to insist that ‘no suspicion whatsoever’ is hanging over him, pointing out that Lord Howard will be grilled under so-called ‘Section 2’ provisions. These are used when the interviewee is not suspected of wrongdoing.

The Serious Fraud Office will say nothing more than that its investigation concerns allegations of corruption in Somalia. It is thought that they centre around an agreement by Soma to make payments to the Somali government, including financial support for the poverty-stricken country to hire expert staff to work on the oil exploration.

Soma denies any wrongdoing and insists it has always conducted its business in a lawful and ethical manner.

Whatever the case, the turn of events must be mortifying for Howard, who was instrumental in setting up the deal that kick-started Soma’s operations. It begs the question why a man with his hugely impressive political credentials is chairing such a company in the first place, when he could be adorning the board of a blue-chip business.

It is easy to see why an obscure firm like Soma, operating in a far-flung part of the world, would want to lure a politician of Howard’s stature. What, though, is in it for him?

Money, is perhaps one answer. Chairmen of small oil companies can receive anything from £50,000 to up to £350,000 in salary. Lord Howard’s fee for the part-time post as chair of Soma is undisclosed, though industry experts say it could be close to £75,000.

The real lure, however, might be the seven million shares he has been awarded. They could theoretically bring him untold rewards — although given the low oil price and the problems caused by the fraud investigation, that does not look likely now.

Howard did not wish to discuss his decision to join Soma, or to comment on the company while the SFO probe is going on. But what is so fascinating is that Soma is far from the peer’s only unusual boardroom role. He has assembled a stack of business interests since he gave up full-time politics five years ago at 68.

His post-politics CV is a hotchpotch of jobs at small companies floating around the nether reaches of the City, some of which seem to have an unerring knack for landing in hot water.

These include a senior directorship at an outfit called Quindell — which used to process insurance claims for law firms and insurance companies — and will now concentrate on ‘telematics’, or installing black boxes in vehicles to monitor how well motorists drive.

Quindell is a name all too familiar to legions of small investors who lost heavily on its shares — the company shed more than 90 per cent of its £2.7 billion value within a year — after it became enmeshed in one of the worst stock market scandals of recent years.

The Serious Fraud Office recently announced it is sending its bloodhounds in there, too, to investigate ‘business and accounting practices’ after the firm reported a £238 million loss and a £157 million write-off on its assets.

The accounting regulator the Financial Reporting Council has also investigated Quindell, which is being probed by City watchdog the Financial Conduct Authority as well.

Lord Howard cannot be blamed for any of this, for the very good reason that he was not on the board at the time the business practices under investigation took place. Indeed, under the new management shares have recovered a small part of the lost ground. Yet his appointment this year is intriguing nonetheless.

He was brought in by Quindell’s new chairman Richard Rose. The pair had previously rubbed shoulders round the boardroom table of car hire group Helphire — another company with a troubled record.

At Helphire, Rose was chairman and Howard, who joined in 2009, was a £47,000-a-year, part-time, non-executive director. They stepped down in 2011 after shareholders became exasperated at falling profits and a plunging share price.

Despite that experience, Rose arrived at Quindell earlier this year and lost no time in bringing on his boardroom buddy Lord Howard.

Yet another entry on Lord Howard’s CV is his role as a director of Entree Gold, a somewhat exotic firm that is listed in Canada and mines for gold in Mongolia.

He was paid around £60,000 at the company last year, which he has ‘voluntarily offered to reduce’ to £40,000 with other directors to cut costs.

Lord Howard has 958,000 shares in Entree that are said on the parliamentary register of members’ interests to be worth less than £50,000 — though they could be worth millions if the company strikes it rich.

Lord Howard, who became a director in 2007, is, according to Entree, motivated by a ‘long-standing interest in Mongolia’. In 2013, the Ulan Bator authorities there awarded him the Order of the Pole Star, the highest honour that can be bestowed on a non-Mongolian.

But the Conservative peer’s globe-trotting commercial instincts do not end even there. He is an adviser to a firm called Orca Exploration, which searches for oil in Tanzania.

On top of that, he finds time to give his services as an advisory board member for private technology company Tetronics International and has been an adviser to City broker Canaccord Genuity.

There is nothing wrong about politicians taking boardroom posts when they step down. Understandably, they are keen to make ‘real money’ after years of impoverishment in politics. Among those to have taken up corporate roles are former chancellor Kenneth Clarke, who fittingly, in view of his fondness for a cigar, was a non-executive at tobacco giant BAT.

Nor is it only Tories who end up gracing oak-panelled offices.

Tony Blair — now worth tens of millions — worked as a highly controversial adviser for investment bank JP Morgan after leaving office on a reported £2.5 million salary, and he still advises a number of foreign governments, some with unpalatable human rights records.

His clients have included PetroSaudi, an oil firm with links to the ruling Saudi royal family and Mubadala, an Abu Dhabi wealth fund.

Less controversially, former Labour minister Patricia Hewitt became a non-executive director at BT after quitting Westminster.

With his formidable CV — and his brilliant mind, charm and indisputable tenacity — Lord Howard could have had his pick of any number of top directorships.

Why then is he swimming at the bottom of the corporate pond in sectors such as oil drilling and gold mining that are notoriously risky and prone to controversy?

It may be that he is genuinely gripped by the resources industry, and the troubled, but fascinating, countries in which it operates.

In the case of Helphire and Quindell, it may be that his interest was piqued by his experience of dealing with personal accident and injury cases as a barrister.

Perhaps, too, there is an element of naivety about business after years spent in the West- minster bubble.

For Howard is a decent man known for loyalty to friends and colleagues. Surely the real sadness is that, if his motivation was to ensure a secure old age, his hopes of a big payday have so far been in vain.

Perhaps he deserves better luck in the future.