Russia’s troll identities were more sophisticated than anyone thought

By The Verge

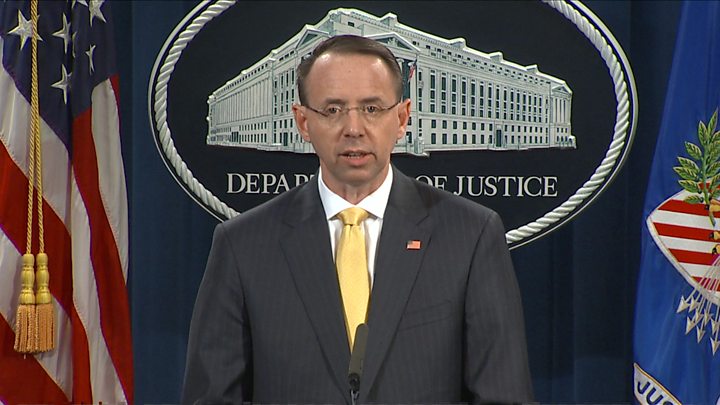

The Russian troll farm has been hit with its first major indictment. Today, special counsel Robert Mueller laid out his criminal case against Russia’s Internet Research Agency, charging that the agency engaged in a sustained campaign to influence the 2016 presidential election. It’s a major shift for the organization, which has largely escaped blowback from the US, and it gives us the best look yet into how the Russian influence campaign actually played out.

One of the most surprising lessons of the indictment is just how seriously the Russians took their fake identities. We might associate troll accounts with spam or weird visuals, but at least some of the accounts described by Mueller were backed up by full-scale identity theft. According to the indictment, defendants used stolen Social Security numbers to build entire false personas, complete with fraudulent photo IDs and PayPal accounts. Crucially, the stolen Social Security numbers meant all of it was happening in a real US citizen’s name. If anyone looked into the person behind the account, they’d see a long paper trail and plenty of government-issued verification to settle their suspicions.

None of this was particularly difficult for the Russians to find. There are hundreds of millions of Social Security numbers circulating in criminal forums, so they would have had their pick. Fake driver’s licenses can be bought for less than $100 in whatever name you like. The Russians seem to have also received help from a California man named Richard Pinedo, who’s been indicted for selling bank account numbers linked to the stolen identities.

The trickiest thing would have been the newly created financial accounts, used to funnel money to political operations in the US, but those accounts wouldn’t have looked suspicious from the outside. The name and Social Security number might be stolen, but they matched each other, and the money and transactions were all real.

(Paypal appears to have cooperated with the special counsel in unspooling the scheme. “PayPal is intensely focused on combating and preventing the illicit use of our services,” the company said in a statement. “We work closely with law enforcement, and did so in this matter, to identify, investigate and stop improper or potentially illegal activity.”)

Even the troll’s internet activity would have looked normal from the outside. According to the indictment, one of the first things the Internet Research Agency did was establish a VPN (or virtual private network) within US borders, allowing them to route all activity through a Stateside intermediary. To anyone in the US, it would have looked like an American citizen visiting a real-name account from an American IP address.

That’s a big shift from how we’ve thought of Russian interference for the past year, and it makes things much harder for Facebook, Twitter, and the rest of the internet. When tech companies were called before Congress in November, the focus was on the most obvious troll activity. There were political ads bought in rubles and accounts maintained from Russian IP addresses. Facebook and Twitter were clearly unprepared for an influence campaign of this scale, but the threat seemed equally haphazard. How hard is it to flag Russian IP addresses?

Stopping this kind of fake account is much harder, and it cuts at the heart of how identity works on networks like Facebook. We know how to look for malware or scams, but these accounts weren’t doing anything out of bounds for a regular user. We know how to look for bots, but these accounts were directed by real humans. We know how to verify identities, but with a photo ID and a valid Social Security number, these trolls would have passed every verification test in the industry. It takes effort to establish this kind of identity, which means you can’t run millions at once — but with the viral lift from a social network, you don’t have to.

It’s hard to know how to protect against that. Unspooling this particular campaign meant following the same group across multiple continents, with untold court orders applying the full force of law over more than a year. How do you pull the same trick on a smaller campaign without the same geopolitical stakes? How do we keep social networks from being overwhelmed by disinformation? They’re hard questions, and as Facebook scrambles to win back trust, I get the sense we’re nowhere near an answer.