The Political Logic Behind Somalia’s Fragmentation

For three decades, the international community has funnelled billions into rebuilding the Somali state. Yet, the result is not a functioning government, but a sophisticated marketplace of chaos, a hollow shell where power is traded, institutions are weaponized, and the very concept of national sovereignty is sabotaged from within. The international community has fundamentally misread the situation. Somalia’s fragility is not an accident to be fixed, but a deliberately sustained system from which powerful players profit. Building a normal state would destroy that system, so those actors sabotage it. Therefore, standard state-building is doomed unless it first addresses this political reality.

The 2012 Provisional Constitution was heralded as a new dawn. Instead, its deliberate ambiguities on federalism have become the primary battlefield. As noted in an article by the World Politics Review, these ambiguities were not oversights but strategic instruments. Successive regimes in Mogadishu have not sought to build a shared vision upon this framework but have weaponized it to centralize power while undermining federal member states. This has birthed what Somali analysts rightly call an “exclusive club”, a political system divorced from public accountability, where parliament operates as a transactional bazaar and the rule of law is an alien concept.

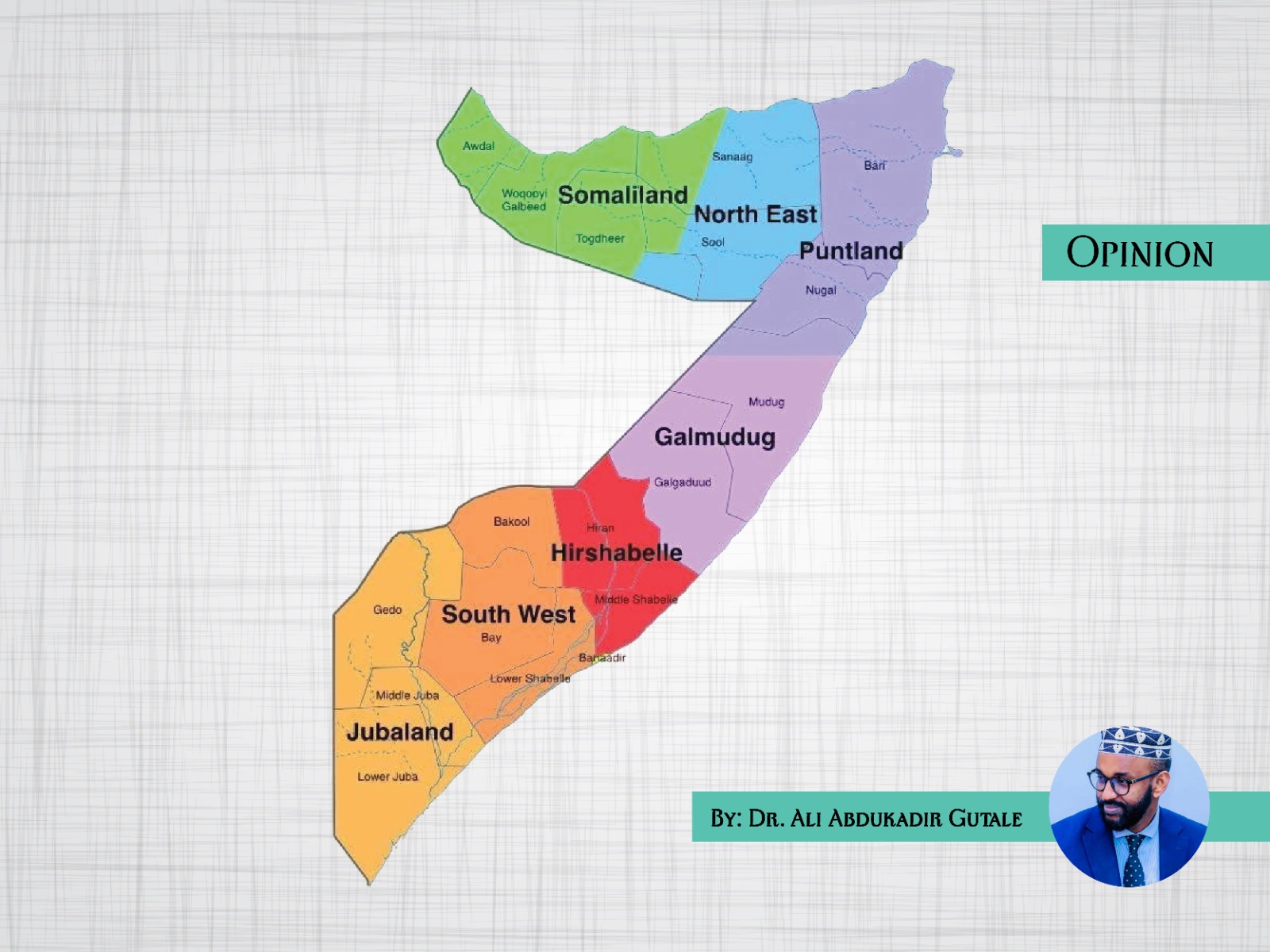

To understand why this club is so resilient, one must look beyond the 1991 collapse. Somalia’s fragmentation into clan-based fiefdoms is not a new catastrophe but a reversion to a pre-colonial norm. The post-1991 landscape of Somaliland, Puntland, and later, the fabricated federal states, represents the re-emergence of clan republics. The modern federal system has simply given a formal, legal structure to long-standing clan divisions, creating a framework for what are, in practice, rival clan-based territories. The conflict between Mogadishu and, say, Puntland, is therefore not a simple policy dispute; it is a clan-based sovereignty struggle decades in the making.

This historical reality finds its perfect theoretical explanation in Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson’s seminal work, Why Nations Fail. They posit those extractive institutions, which concentrate power and wealth for a narrow elite, condemn nations to poverty and strife. Somalia is a textbook case of their thesis. What is often mislabelled as “decentralization” is in fact a fragmented, extractive equilibrium. Power is distributed not to foster pluralism, but to facilitate elite bargains for resource extraction: control of ports, skimming of aid, and informal taxation. The political settlement is fundamentally anti-state because a centralized, impersonal authority with a monopoly on violence and justice would dismantle the entire extractive edifice, including the profitable marketplace of insecurity.

This extractive system sabotages any reform that threatens its logic. Elites block a transparent national tax system to preserve wealth through informal bribes, cling to indirect clan-based elections to control patronage networks, and prevent the creation of a truly national army, as it would sever the vital link between clan militias and political power, the very foundation of their influence.

The critical contrast has long been Somaliland. Its historical achievement of relative stability is not a mystery; isolated from the flood of international aid and top-down engineering that corrupted the south, it was forced into a fiscally bargained, bottom-up political settlement. This allowed it to develop a more centralized monopoly on violence and functional institutions, establishing itself as a cohesive clan-state project.

In recent years, however, this relative stability has proven neither static nor guaranteed. Somaliland now contends with significant internal pressures that reveal the fragility of its model. The newly formed “Northwest” federal member state, directly challenging Hargeisa’s authority, and the rising anti-secessionist sentiment in the Awdal region prove that the same clan-based fragmentations that destabilized the south are deeply embedded in its own political fabric. Its cohesion is now under direct internal assault.

This presents the evolving paradox for Somali unity. The entity once hailed as the region’s most stable model is itself grappling with the very forces of fragmentation it claimed to have overcome. Its stability was historically derived in part from not being entangled in the south’s destructive politics, but it is not immune to them. This reality complicates any simplistic narrative of Somaliland as a ready-made alternative and highlights the pervasive, enduring challenge of building a legitimate and inclusive state structure across all Somali territories.

Embedded within this political economy of extraction lies an existential susceptibility to complete fragmentation into smaller, antagonistic clan-based entities. This is not merely a risk of prolonged instability, but a tangible trajectory fuelled by the very logic of the elite marketplace. The constitutional weaponization of federalism, the century-old clan sovereignty struggles, and the economic incentives for local elites to control ports, aid flows, and taxation, all converge to make disintegration a viable, and for some, a profitable, political outcome. The precedent of Somaliland’s recognition by Israel and the emerging fractures within it, alongside the perpetual tensions between Mogadishu and federal states like Puntland and Jubaland, demonstrate that the centrifugal forces are already actively dismantling the nation. Without a fundamental disruption of the extractive system that rewards fragmentation, the evolution from a “failed state” to a fully fragmented archipelago of clan republics becomes not a possibility, but the inevitable culmination of its political marketplace, a terminal threat to the very idea of a unified Somali nation.

Herein lies the grand failure of the international paradigm. Channelling billions into training soldiers, drafting laws, and conducting technical workshops is futile because it bypasses the core extractive political settlement. We are building facades of institutions on quicksand. The problem is not a lack of state capacity, but the presence of a powerful political elite that actively profits from preventing a state from forming.

Therefore, the revival of a unified Somalia is impossible without a prior, radical transformation in two areas: first, the deliberate construction of impersonal, rules-based institutions that break the clan-to-cash pipeline; and second, the cultivation of a political elite willing to trade clan patronage for genuine national sovereignty. This is a generational task, not a project cycle.

Continuing the current path is not merely wasteful; it is destructive. It legitimizes extractive elites, entrenches fragmentation, and makes a mockery of the Somali people’s suffering. We must stop trying to build a state for Somalia and start asking how to foster the political conditions where Somalis can build one for themselves. Until then, our engagement only deepens the quagmire. The choice is not between different state-building blueprints, but between confronting this hard truth or perpetuating a dangerous, expensive charade.