CBS News goes inside Somali hospitals where climate change-induced hunger is killing children

CBS NEWS|BAIDOA: Almost half of the 16 million people who live in Somalia are facing extreme hunger. More than a third of the east African nation’s 5 million children under the age of five are acutely malnourished. Hunger and the health complications it causes are putting one Somali child in a health care facility every minute.

Somalia’s children are among the youngest victims of climate change. CBS News visited an intensive care ward where every child was under five, all of them hospitalized by the climate change-induced drought that has left their nation starving.

The security situation in Somalia, where the al Qaeda-linked al-Shabaab terror group holds significant ground, blocking humanitarian work, is contributing to the catastrophe, but other human actions are also to blame. A 2020 survey ranked Somalia as the second-most vulnerable nation to the impacts of climate change in the world, and the drought is how that risk manifests.

After more than two years without rain, there is nothing left to eat.

Among the youngest in the hospital in Baidoa, in Somalia’s parched south, was Amir. Just over a year old, he was not only underweight but suffering with diarrhea and a fever. If he hadn’t made it into the hospital when he did, one of the doctors said he would likely have died.

The medics see multiple cases like Amir every single day. As we started reporting at the hospital, another child was being admitted, severely malnourished.

It was the same at the nearby Bay Hospital, where beds fill up quickly in the paediatric ICU ward.

There, 10-month-old Fatun was being treated for severe malnutrition complicated by pneumonia. She opened her mouth to cry, but her frail body was too weak. She couldn’t even make tears, only a gaping, silent scream.

Two-year-old Naema was defying the odds. She was making a slow recovery, but her body was still difficult to see, covered in what looked like third-degree burns. The sores were actually the result of kwashiorkor, a form of severe malnutrition in which a person’s body is so deprived of protein, that their skin tissue swells up and then bursts open. It left Naema covered in weeping, infected wounds.

Then another new arrival came in, and it was a medical emergency.

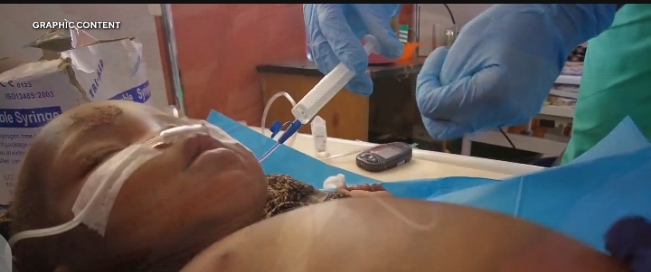

Two-year-old Malyun was dying. Her blood oxygen level was dangerously low — 37 when it should have been closer to 100. She was bloated from severe malnutrition.

Hunger had devoured her, and her body was turning on itself. With her blood sugar crashing, the toddler was so limp that she didn’t even flinch as a nurse inserted an IV in a bid to save her life.

The little girl’s mother Farhiya Adan was sick with worry, and her grandmother was too upset to keep watching as the hospital staff worked with practiced urgency.

Many of the children being admitted to Somalia’s hospitals don’t make it.

Dr. Abdullahi Yusuf told us that, in this day and age, it’s simply “not fair” that children should lack access to food and basic medical care.

But many families just don’t make the long trek to a hospital in time, Dr. Said Yusuf told CBS News.

“Sometimes they come with a child dying already on the road,” he said, acknowledging the emotional strain the crisis has put on him and his colleagues. “Just seeing a child dying in front of you daily… we sometimes have nightmares.”

And the nightmares keep coming.

About 36 hours later, Malyun, who spent her whole, short life hungry, went into septic shock. We were there as she took her final, strained breaths.

United Nations humanitarian chief Martin Griffiths warned more than a month ago that he was in “no doubt” that there was already famine in Somalia. A formal famine declaration comes when a region or nation meets certain prescribed criteria on mortality rates, insecurity and other metrics. It doesn’t trigger a legal response, but it will often galvanize the international community to help more urgently.

The last time a famine was declared in Somalia, in 2011, more than 250,000 people died for lack of nutrition, half of them under the age of five. The world vowed never to let it happen again.

Doctors on the ground have told CBS News for weeks that they’ve been expecting a formal declaration of famine in some Somali regions during November, but Malyun’s story is devastatingly clear evidence that for many children, if that ever comes, it will come too late.