South Sudan most dangerous for aid workers-report

By Fauxile Kibet

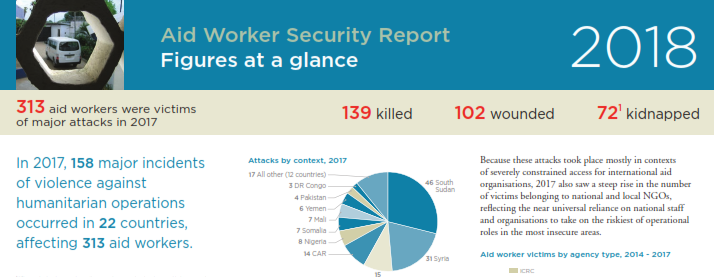

Almost one in three of the 158 attacks on aid workers that occurred last year globally was reported in South Sudan, a new report has said.

The Humanitarian Outcomes 2018 report notes that 46 humanitarian workers were killed in South Sudan in 2017 making it the deadliest country for humanitarian actors three years in a row.

Syria, Afghanistan and the Central African Republic were listed the next most dangerous, followed by Nigeria and Somalia.

“It’s the third consecutive year that South Sudan tops the global list, underscoring the complexities in delivering aid in this war, and the impunity with which armed actors operate when attacking aid workers,” said Jan Egeland, Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC).

Record numbers of humanitarians were killed by gunfire in South Sudan last year, with 24 dying of gunshot wounds.

2017 also witnessed an increase in detention of aid workers by parties to the conflict. Other violent attacks included physical assaults and armed robberies.

“Aid workers are protected by international law and must not be used as pawns in South Sudan’s conflict. Violence against aid workers paralyses our lifesaving work,” said Egeland.

In Somalia, 7 aid workers were killed in 2017 largely attributed to the militant group Al-Shaabab. The group, the report said viewed humanitarian workers as spies and that the loot from humanitarian actors provided income for the group to support its operations.

One hundred aid workers have lost their lives since the conflict broke out in December 2013, with South Sudanese staff at the highest risk. They often work in the hardest-to-reach locations, which can also be the most dangerous.

Conflict has meant that, on occasion, relief organisations have been forced to temporarily pull out of areas until the security situation improves, often resulting in the suspension of critical aid delivery, like food and medicine.

Food distributions are a lifeline for tens of thousands of people, and helped to reverse famine in 2017. However, food experts have pointed to the possibility of famine again this year, if access to communities on the brink of starvation is not improved.

“We are cautiously optimistic about last week’s peace deal signing. We need to see positive action now for it to materialise. The peace deal must result in improved access for humanitarians to communities caught in conflict areas,” said Egeland. “Furthermore, it must see perpetrators being held to account for attacks against aid workers.”