Storyteller of the savannah

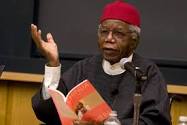

The founding father of African writing in English, he challenged the perspective of colonialist white writers and fell foul of successive regimes in Nigeria. Just turned 70 and living in the US, his latest novel is a return to his troubled homeland. Maya Jaggi report.

While Nelson Mandela was serving 27 years in jail, he drew consolation and strength, he says, from a writer “in whose company the prison walls fell down”. For Mandela, the greatness of Chinua Achebe, founding father of the modern African novel in English, lies in his having “brought Africa to the world” while remaining rooted as an African. As the Nigerian Achebe used his pen to free the continent from its past, said the former South African president, “both of us, in our differing circumstances within the context of white domination of our continent, became freedom fighters”.

Mandela’s tribute was videoed in honour of Achebe’s 70th birthday on Thursday, and sent to leafy Bard College in upstate New York, where Achebe is professor of languages and literature. The professor, born into the 10m-strong Igbo nation of eastern Nigeria, sat through a two-day celebration in the red fez-like hat of the Igbo elder. He was sent greetings from the UN secretary-general, Kofi Annan, and Nigeria’s first civilian leader in 16 years, President Olusegun Obasanjo, and homage was paid by fellow writers, including three Nobel laureates: Toni Morrison, Wole Soyinka and, in absentia, Nadine Gordimer. It is rare, Achebe remarked later with gentle irony, to hear such concerted singing of your praises “unless you’re a Third World dictator”.

This summer in the US, Achebe brought out a volume of essays, Home And Exile, to be published in Britain in January. In it, he hankers for the homeland where his fiction is rooted – “where I could see my work cut out for me”. He places his oeuvre within Salman Rushdie’s notion of “the empire writes back”: postcolonial writers countering Europe’s fictions by seizing the right to tell their own story.

Achebe is known across continents for his landmark first novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), a tale told “from the inside” about the destructive impact of European Christianity on precolonial Igbo culture amid the scramble for Africa in the 1890s. Published on the eve of Nigerian independence in 1960 when its author was 28, it helped reshape literature in the English-speaking world, but it was not the first novel by an African: precursors included fellow Nigerians Amos Tutuola and Cyprian Ekwensi, South Africa’s Peter Abrahams and, in French, Senegal’s Ousmane Sembene and Cameroon’s Camera Laye. It has sold more than 10m copies internationally and been translated into 45 languages, making it one of the most widely read novels of the 20th century. A biography by Ezenwa-Ohaeto was published in 1997 (published by James Currey).

For Soyinka, Things Fall Apart was “the first novel in English which spoke from the interior of an African character, rather than portraying the African as exotic, as the white man would see him”. Nigeria’s two literary giants are friends, though rivalry is often assumed: the critic Chinweizu deems Achebe superior in “decolonising the mind”, while oth ers judge Soyinka’s politics more “radical”. When Soyinka won Africa’s first Nobel for literature in 1986, Achebe warmly congratulated him, but put the Swedish accolade in perspective as a “European prize”. Last year they were billed with Derek Walcott at the Word festival in London’s Hackney Empire as “two Nobel laureates and a legend”.

Another Nobel laureate, Toni Morrison, says Achebe sparked her “love affair with African literature” and was a major influence on her beginnings as a writer. “He inhabited his world in a way that I didn’t inhabit mine – the things he could take for granted – insisting on writing outside the white gaze, not against it,” she says. “His courage and generosity were made manifest in the work; and that’s difficult to do: to talk about devastation and evil in such a way that the text itself isn’t evil or devastating.”

Achebe’s arguments are delivered with force but in a deceptively soft voice. Though he can seem melancholic, his talk is punctuated by laughter and shafts of dry humour. As his birthday showed, he can bring together people who agree on nothing but their affection for him. Chinweizu, of a Nigerian school of critics known as the Bolekaja Boys (street slang for “jump up and fight”), sat alongside Soyinka, whom they once pilloried as a “Euro-assimilationist”. They were in turn put down as “neo-tarzanist primitivists”. Soyinka shared a platform with his intellectual sparring partner, the historian Ali Mazrui, as they declared themselves on their “best behaviour”.

In Home And Exile, Achebe has stepped further into autobiography. “Maybe that’s what turning 70 does, though I don’t feel any different; you tend to move in the direction of memoir. The ideas I wanted to pursue took an autobiographical turn because the final authority I could bring was that of my own experience.”

He was born in 1930 in Ogidi, an Igbo village near the Niger, 400 miles east of Lagos. The fifth of six children, he was baptized Albert Chinualumogu, but “dropped the tribute to Victorian England”. His father, Isaiah, was a Christian convert and evangelist, with “gallows humour”. He and Achebe’s mother, Janet, were “ardent followers, but not fanatical”; while the family sang hymns, Isaiah’s relatives offered food to what he considered idols. “An accommodation with the church developed after initial struggle,” says Achebe. “Common sense and the strength of Igbo culture slowly reasserted themselves.”

His parents were “extremely profound people, of few words but strong convictions; great believers in education”; with little resources, they sent their children to school. Chike Momah, a classmate, recalls Albert Achebe as a brilliant conversationalist – a trait shared with his father – and says his headmaster predicted “he would make the rain that would drench us all”.

“We lived at the crossroads of cultures”, wrote Achebe, who learned English at eight and whose passport declared him a British Protected Person (“an arrogant lie because I never did ask anyone to protect me”). He contrasts the slow, quiet education of his home village with the louder, formal education of mission school. “I knew I wanted to understand the life of the society, the stories and masquerades,” he says. “It’s curious how brainwashed we were; quite a bit of my growing up was discovering that fact.”

In a 1973 essay, Named For Victoria, Queen Of England, he describes Things Fall Apart as “an act of atonement with my past, the ritual return and homage of a prodigal son”. He says: “It’s that fascination with the scraps and pieces of information I could gather about my ancestors that developed into a desire to write my story. Colonial education was saying there was nothing worth much in my society, and I was beginning to question that, to see there were things that were beautiful even in the ‘heathen’.”

Enrolled at Ibadan university to study medicine (“a false step”), Achebe switched to the arts. In the new essay “Home Under Imperial Fire”, he describes how he was spurred to write partly by being made to read Joyce Cary’s 1939 novel Mister Johnson, with its “bumbling idiot” of a Nigerian character: “It began to dawn on me that although fiction was undoubtedly fictitious, it could also be true or false.” He explains: “I’d read so-called ‘African novels’ in school, by Rider Haggard and John Buchan, in which white people were surrounded by savages but managed to come out on top. But I didn’t recognise them as relating to me until I read Mister Johnson: this book was not talking about a vague place called Africa but about southern Nigeria. I said, ‘wait, that means here; this is our story’. It brought the whole thing home to me: this story is not true, so is it possible the others are not either? It opened up a new way of looking at literature.”

That “landmark rebellion” caught a wider moment. “The 50s were also the time when the ferment for freedom was at its highest. India was independent, so it was only a matter of time for west Africa. The second world war was fought for freedom; when they told us to collect pine kernels for the war effort, they said each one would put a nail in Hitler’s coffin. Nigerians returning home from the war asked, ‘where’s the freedom we were told about?’ So the two things were together: the political ferment and the revolution in the classroom.” Achebe credits Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952) with opening “the floodgates to modern west African writing” in the 50s. “It’s as if this thing was waiting to be told; the time was ripe,” he says.

The precolonial society of Things Fall Apart, whose tragic hero Okonkwo mounts doomed resistance to encroaching European power, was far from idyllic. Achebe insists on “an unflinching consciousness of the flaws that blemished our inheritance”. He says: “Of all the things I remember, that was the clearest: I must not make this story look nicer than it was. I went out of my way to gather all the negative things, to describe them as I think they were – good and bad – and ordinary human beings as neither demons nor angels. I dare anybody to say, ‘these people are not human’.”

He wrote in English, as arguments against using the language of the coloniser were gathering steam. “It was part of the logic of my situation – like the inevitability of my writing at all – of countering stories about us in the same language in which they were written. Writing in English is a painful choice. But you don’t take up a language in order to punish it; that language becomes part of you. And you can’t use language at a distance; you introduce English and Igbo into a conversation, as they are in my daily life – that’s fascinating.” The Igbo art of storytelling became central to the tale, since “proverbs are the palm oil with which words are eaten”. Achebe, who writes poetry in both Igbo and English, says, “I insist on both”.

For the critic Simon Gikandi, Achebe showed that “the future of African writing did not lie in sim ple imitation of European forms but in the fusion of such forms with oral traditions”. Kwame Anthony Appiah, professor of Afro-American studies and philosophy at Harvard, says Achebe “solved with deceptive ease difficult technical questions, such as how you represent the language of one society in the language of a very different one. His use of a variety of registers of English came to be seen as obvious; it set modern African literature in English on a certain path.” The Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who in the 80s renounced writing fiction in English in favour of Gikuyu, believes “Achebe created a third position out of the tension between Igbo and English, which becomes the base of his creativity; you feel there’s an African voice in his work being rendered in English.”

After working as a radio producer, Achebe had come to London in 1957 to train at the BBC staff school. “It was the first time I saw the great British empire at close quarters, and it brought England a couple of pegs down: to find a white man in dirty overalls filling holes in the road was unbelievable.” He sent the longhand manuscript of Things Fall Apart to William Heinemann, where a reader pronounced it “the best first novel since the war”. But at a time when many in the metropolis believed, according to the publisher James Currey, that “an African could not reach the standards of an English publishing house”, a modest 2,000 hardbacks were printed.

Then in 1962 Heinemann Educational Books launched the African Writers Series with four novels, including Things Fall Apart and its sequel, No Longer At Ease – set on the cusp of independence, in the era of Okonkwo’s grandson. It was an inexpensive paperback imprint that emulated the Penguin revolution down to its orange covers, while selling 80% of copies in Africa and keeping titles in print. It proved that a readership existed, and was a signal for Africa’s writers, says Achebe, who selected the first 100 titles.

He was able to do what was an unpaid job as series editor for 10 years because he had jobs in broadcasting, and then academia. (The late Heinemann director Alan Hill recalled him as “the very image of a modern Nigerian yuppie”, with sharp suit, dark glasses and a Jaguar.) “I thought it was of the utmost importance,” Achebe explains. “People in England were sceptical, so I knew I was a conspirator. I was naive enough to think that if you do good work, you’ll get your reward in heaven.”

For Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Achebe “made a whole generation of African people believe in themselves and in the possibility of their being writers”. The Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah says he learned his craft from him: “He taught us a way of integrating what we know from being African with what we’ve become – hybrids of a kind.”

After travelling through southern Africa on a Rockefeller scholarship in 1960, “the winds of change in my sails”, (vexing the Northern Rhodesian authorities by sitting in the front of a segregated bus near Victoria Falls), Achebe became the first director of Voice of Nigeria, the state-run radio’s external arm, where he remained till the eve of the Biafran war in 1966. He met his wife to be, Christie Chinwe, then a student, in Broadcasting House in Lagos, where she had a holiday job. She later became a professor.

The couple have two sons and two daughters (one of whom, Chinelo, is a writer), and two grandchildren. “Christie saves my life every other day,” says Achebe. “And she suffers my pain more than I do. When I had the accident, she left her classroom and never really got back.” Though she is now a psychology professor at Bard, she was forced to leave her field of education, a sacrifice Achebe feels keenly. “When I was drifting in and out of consciousness I remember saying I wanted her to go with me – to England. That’s been her life ever since.”

After his third novel, Arrow of God (1964), set in Igboland in the 1920s – which won the Jock Campbell New Statesman award – Achebe wrote a satire on corruption in a fictitious African country following the “collusive swindle that was independence”. A Man Of The People (1966) proved prescient about Nigeria’s first attempted coup, which happened two days before its publication. Some thought the author complicit in the Igbo-instigated coup. He obviously wasn’t. As massacres spread against Igbos in northern and western Nigeria, Achebe and his family went into hiding. They fled Lagos for Igboland, where Achebe took up a post at the university in Nsukka.

On the eve of the Biafran war of 1967-70, Achebe went on a peace-seeking mission to President Leopold Senghor of Senegal, founder-poet of the francophone Negritude movement. “I was sent by the government of Biafra because I was also a writer, in the hope of stopping the war,” Achebe recalls. “We talked about Biafra for 10 minutes and literature for two hours.” But as war broke out, Achebe served on more diplomatic missions for the breakaway Biafran republic. “I was deeply disappointed with what was happening in Nigeria,” he says. “I was ready just to go to my village, but I did whatever I was asked.”

The war was shattering for Achebe; his house was bombed and his best friend, the poet Christopher Okigbo, was killed. On the “wrong side” when the secessionists were crushed, Achebe was refused a passport, but finally left in 1972, for professorships in the US before returning to Nsukka as professor of English in 1976. He had first visited the US in the early 60s, when he met writers including Ralph Ellison and Langston Hughes. His unsentimental recovery of the dignity of Africa’s past chimed with the notion of “black is beautiful” among African-Americans brought up to see Africa as an embarrassment. John Edgar Wideman recalls the shock of finding “language being refashioned from another centre I didn’t know existed”.

Achebe embraced writers of the diaspora, calling Africa a “spiritual phenomenon born of a painful history… which binds every Black person”. He launched the journal Okike, and later a bilingual Igbo journal. Beware Soul Brother (1971), which won the Commonwealth poetry prize, and Girls At War And Other Stories (1972), both reflected the trauma of the civil war. He also published children’s books, essays and a heartfelt polemic, The Trouble With Nigeria (1983), when he became involved in party politics. But there was a gap of 21 years before his fifth novel.

Lyn Innes, professor of postcolonial literatures at the University of Kent, co-edited two Heinemann African anthologies with Achebe. In her view, “his fiction was concerned with portraying a society, and Nigerian society was so totally destabilised, he found it difficult to write a sustained work – only fragments”. Achebe says: “I don’t think it damaged my work; it gave it a new direction for a while into poetry and short stories. I regard all of them equally.”

Achebe’s friend James Baldwin savoured the elegance of Achebe’s essays as “not a mere pleasure but a benefaction”. The dissection in the essays of Europe’s self-serving myths of Africa, and how they shored up slavery and empire, are a prelude to Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and Toni Morrison’s scrutiny of the black presence in American literature in Playing In The Dark (1992). In a famous lecture on Heart Of Darkness in Massachusetts in 1975 (included in Hopes and Impediments, 1988) he described Joseph Conrad as a “thoroughgoing racist”, disputing that a novel which dehumanises a portion of the human race could be called a great work of art (one American professor stalked off, saying, “How dare you?”).

Achebe attacked the “perverse arrogance” of reducing Africa to a “setting and backdrop which eliminates the African as human factor”. In his view: “Conrad saw and condemned the evil of imperial exploitation but was strangely unaware of the racism on which it sharpened its tooth.”

“I’m surprised it’s gone on being controversial, but it has,” he says. Some still argue that to accuse Conrad of racism is anachronistic. Achebe responds: “Long before Conrad, there were people who refused to be racist. Time does contribute something to what we think, but good people are never prisoners of their era.” As for Conrad’s prose: “It would have been better if the beautiful prose were used to unite the human race, rather than separate it. The best works, whether written or oral, seem to me to have an intrinsic morality; it’s not Sunday school morality, but I’ve not encountered any good art that promotes genocide.”

Achebe’s stand is sometimes misunderstood as censorship. “I’m not Ayatollah Khomeini,” he objects. “I don’t believe in banning books, but they should be read carefully. Far from wanting the novel banned, I teach it.” By the same token, he advocates closer reading of VS Naipaul (“a new Conrad… purveyor of the old comforting myths of race”) and Elspeth Huxley (“the griot [story-telling caste] for white settlers”).

In his introduction, with poems, to Another Africa (1998, Lund Humphries), photographs by Robert Lyons, Achebe writes: “The vast arsenal of derogatory images of Africa amassed to defend the slave trade and, later, colonisation, gave the world not only a literary tradition that is now, happily defunct, but also a particular way of looking (or rather not looking) at Africa and Africans.” He warns against the enduring tendency to act for, or upon, Africa while failing to listen to its inhabitants.

In a 1998 lecture to the World Bank, he urged the cancellation of Third World debt, having told western bankers in Paris a decade before: “You talk about ‘structural adjustment’ as if Africa was some kind of laboratory… But Africa is people!” Achebe has called himself a “missionary in reverse”. Lyn Innes, who sat in on his classes in the US in the 1970s, says, “ill-informed students would ask outrageous questions about cannibalism, or from reading his work as anthropology not literature. But he was always patient and tolerant, trying to turn them around.”

Achebe’s fifth novel, Anthills Of The Savannah (1987), revived his reputation in Britain when it was shortlisted for the Booker. Set in a military regime in present-day west Africa, it introduced a female intellectual, the journalist Beatrice, some say in response to criticism of his earlier work. “Feminists would like to take credit; I’ve no objection, but I don’t need anyone to scare me into realising the paradoxical position of women,” says Achebe, who is working on a new novel with women at its heart.

“The female presence is there in all my novels. It seems as if it’s not important – which is the reality of how it looks in Igbo society – till you get to a crisis which threatens survival. When the British came, that was a critical moment; the men fought and lost. But there were events in Igboland where women stopped the British in their tracks. That’s been happening in my fiction; the incremental involvement of women in political matters. It’s not straightforward; it’s a struggle for power.”

Morrison believes Achebe’s early work leaves a lot of space for women, which was like a revelation to her: “the notion here in America is that slavery was about the imprisonment and emasculation of black men. But with Achebe I never felt the male claw grabbing up the entire canvas; there was feminine space where women existed without permission from the man.”

Others could step into that space. Farah, whose novel From A Crooked Rib (1970) was written from the point of view of a circumcised Somali woman, points out that the central consciousness, even of Anthills Of The Savannah, is still male, but says his own writing was partly in response to the absences he felt in Achebe’s oeuvre. He says it was important for someone to deal with the bigger quarrels of Africa and colonialism – “but it left me free to cover quarrels within the community – between men and women”.

Last year Achebe visited Nigeria for the first time since his accident. His initial impressions of Lagos were “confusing and very depressing; the place looked deserted, not well looked after, with potholes in the landing strip”. Only after a bitter quarrel was a wheelchair found to take him off the plane. “I went incognito; I didn’t want a red carpet. That’s normally my style because I want to see the country as it is.” Pained, he murmurs the unthinkable: “Maybe somebody wanted me to bribe them.”

In The Trouble With Nigeria, Achebe insisted: “Nigerians are what they are only because their leaders are not what they should be.” He swiped at Gen Obasanjo for his “flamboyant, imaginary” idea of a great Nigeria. On his recent trip, however, Achebe met the general, now civilian president, “to encourage him”. Although Nigeria is “sicker than we feared” (he identifies the Muslim sharia law as the greatest threat to the federation), Achebe clings to hope: “Even Nigerians are not entirely immune from learning from their history.”

He had to steel himself for the 400-mile car journey to Ogidi: “you might suddenly find a ditch in the middle of the road. Life is so unsafe,” he says. “Things had got much worse in nine years; for the first time you saw beggars camped out by the roadside. But I always return to the good things: the whole village had turned out and waited all day.” His arrival was hailed with an artillery salute. “It was a tremendous experience. I almost found myself in tears; there are good things going on. My people deserve better than they’ve had by a long chalk.”

Chinua Achebe’s novels are published by Heinemann International. Home and Exile will be published by Oxford University Press in January.

Life at a glance

Albert Chinualumogu Achebe

Born: November 16 1930, Ogidi, Nigeria.

Education: Church Missionary Society primary school, Ogidi; University College, Ibadan.

Married: 1961 Christie Chinwe Okoli (two daughters Chinelo, Nwando; two sons Ikechukwu, Chidi).

Career: Editor, Heinemann African Writers Series; 1971- founding editor Okike; 1985- emeritus professor of English, University of Nigeria, Nsukka; 1990- Charles P Stevenson Professor, Bard College, New York.

Some books: Fiction: Things Fall Apart (1958), No Longer At Ease (1960), Arrow of God (1964), A Man Of The People (1966), Girls At War (stories, 1972); Anthills Of The Savannah (1987). Poetry: Beware Soul Brother (1971) Another Africa (1998). Essays: The Trouble With Nigeria (1983), Hopes And Impediments (1988), Home And Exile (2000).

Awards: Commonwealth poetry prize, 1979.

Achebe has suffered for challenging just such strongmen in Nigeria. But his present exile has a different cause. In March 1990, only weeks after attending a gathering that anticipated his 60th birthday in the eastern Nigerian town of Nsukka, a car crash on the country’s lethal roads left him paralysed from the waist down, and in a wheelchair. He was airlifted to Britain for surgery (“the damage was so severe they didn’t think I’d survive”), told he would never walk again, and advised to move for therapy to the US, where he took up a professorship at Bard, in Annandale-on-Hudson.

“I thought I’d go home after a year,” he recalls in his clapboard bungalow on campus. “But home has simply got from bad to worse in terms of hospital facilities. I’ve had severe infections, and you need proper antibiotics, not fakes. When you say a country has broken down, that’s what it means.” The annulment of Nigeria’s elections in 1993 by President Ibrahim Babangida militated against his return. A subsequent coup by General Sani Abacha brought even harsher dictatorship – marked by the hanging of the writer Ken Saro-Wiwa in 1995. Last year’s return to democracy has scarcely begun to reverse the country’s decline.

The Guardian Profile Book Review